Judge Bradley Soos asked twice Thursday if the feeble man before him in a Pinal County Superior Courtroom could hear him.

"I think so," said the man, leaning forward, his hands cuffed, his tattoos drooping beneath his red jumpsuit.

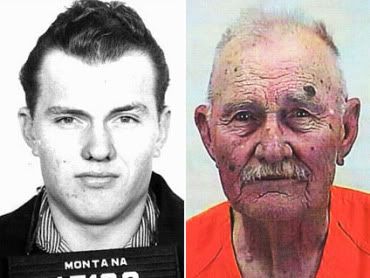

The court knows the man as Frank Dryman, a fugitive from parole, a murderer who shot a man seven times in the back in a small Montana oilfield town in 1951.

His neighbors in Arizona City know him as Victor Houston, the gruff yet charming deacon who ran a wedding chapel, painted signs and sold cactuses and desert knickknacks. He was a notary public. He was on the board of the local Moose Lodge. He graduated from the sheriff's citizens' academy.

In Arizona City, the man everyone saw but few knew well had suddenly become the man who had nearly been hanged in Montana.

In the sleepy community 60 miles south of downtown Phoenix, news spreads fast. One car after another drove by the compound surrounding his wedding chapel Thursday morning, boots hang from the skeleton of a cholla cactus. But beyond knowing him as the quirky man who ran the town's wedding chapel, few really knew much about their neighbor, and no one in town knew him as well as his close friend Patricia Lindholme did.

Not long after she met the man she knew as Vic, he told her he once killed somebody. He told her that it was in a bar fight a long time ago and that he had served his time. She didn't ask questions.

Decades earlier, a 19-year-old Frank Dryman caught a ride with Clarence Pellett, a rotund café owner and father of six, as Dryman hitchhiked from California to Canada in April 1951. When the two arrived in Shelby, Mont., Dryman pulled a .45 caliber pistol. Pellett took off running. Dryman missed with the first shot but felled his victim with the second. Then Dryman walked up to the body and fired six more shots.

A 160-man posse fanned out across northwestern Montana in search of Pellett. They found his body with eight empty shells nearby, about 45 feet from muddy tire tracks in a field.

Authorities caught up to Dryman in Canada the next day, and he signed a confession. Within a week of the murder, he was convicted and sentenced to hang. The state's "galloping gallows," the traveling execution squad, would be coming to Shelby.

The newspaper in town published a special section about the murder, but the hanging never happened. The verdict was thrown out because of the local publicity. After a second trial he was sentenced to a life of hard labor in the state penitentiary. He served 14 years. Two years later, he skipped out on his parole.

"Whatever happened to the infamous Frank Dryman, the cold-blooded murderer?" the Great Falls Tribune asked in an article written in 1977.

In the three decades that Frank Dryman lived as Victor Houston, his only brush with the law was a speeding ticket from the Pinal County Sheriff's Office. He tended to his own business, spoke his mind occasionally and built a humble life as a sign-painter and a father.

He paid his yearly dues to the Chamber of Commerce. Most businesses around town display signs painted by Dryman. No one knew it was a trade he picked up in prison.

His daughter and stepdaughter attended local schools in the 1990s, when Houston participated in a parent-teacher organization and donated signs to carnivals. Most in town saw Vic as a rough but active member of the community. Lindholme saw him differently.

"There was something so sad coming off of him," she said. "I saw this deteriorating old man, and there was nobody to help him."

He was legally blind and could barely hear. He had liver failure and had survived prostate cancer. In recent weeks, he began asking Lindholme to take care of his affairs. He wrote a will on March 16 and asked her to be its executor. But looking back, Lindholme said, she still doesn't think her friend Vic knew what was coming.

Neither did Clem Pellett, who was born two years after his grandfather was shot to death. Clem's father never spoke about the murder but warned Clem to never pick up hitchhikers. It wasn't until he cleaned out his mother's Chandler home that Pellett, an oral surgeon from Washington, discovered a box of mementoes and the newspaper clippings on his grandfather's death.

Pellett called local Montana newspapers and began requesting more clippings. He looked through transcripts of the trial, where his wife found a description of Dryman's tattoos. He requested records from the Montana Department of Corrections and the parole board. Then he began searching for Dryman himself. Before long, Pellett received a call from a family friend that a private investigator had found Dryman.

"I was just flabbergasted. I thought he was dead," Pellett said.

Patrick Cote, a private investigator based in Casa Grande, Arizona, tracked Dryman's Social Security number to the wedding chapel. Cote went looking for Frank Valentine, another alias. He found Victor Houston. His tattoos were similar and the stories seemed to match.

"Dryman and Houston were one and the same," Cote wrote in his report to the Pellett family.

It took Pinal County sheriff's deputies about 30 minutes to get a confession.

The tattoos were faded and his fingerprints weren't in the national database. But after the detectives told Houston that they were getting an analyst to compare his prints to those of the missing Frank Dryman, he broke down and told the truth.

On Thursday, two days after his arrest, Dryman signed a waiver to forfeit his rights to extradition proceedings. The state of Montana will come to Arizona to pick up the fragile old man. The state's parole board then has the option of re-paroling him, sending him to prison with the option to return before the board or requiring him to serve the full life sentence.

Lindholme said if he does return to prison, she isn't sure how long he'll last. With his recent money problems and the loss of his license, life in Arizona City has been hard.

Lindholme has been in touch with his daughter, who lives in New Mexico, and his siblings. They all knew of his past, though how much his daughter knew is unclear. Dryman even told a detention officer that he was relieved to not have to run anymore, said Tamatha Villar, a sheriff's department spokeswoman.

"Vic was chased by demons all his life," Lindholme said. "Let's face it, all he had to do was abide by the rules, and he couldn't do it."